Last month at WordCamp US in Portland, OR, all of the Core Committers in attendance met after lunch for an informal gathering. There was no agenda, but the goal of the the meeting was essentially to meet (some for the first time), spend time together, and discuss anything that may be on our minds.

If you’re interested, the full meeting notes have been published on the Make WordPress Core site. This post is to follow up on two action items that we took away.

- Core Committers need to do a better job of documenting their work, responsibilities, and knowledge sharing through: blogging on their personal sites of course!

- There is only very rudimentary documentation around the act of committing to the

wordpress-developrepository, at best. This is mainly the case because everyone’s workflow and tool set is unique to them. The best way to address this? ☝️ See #1.

I am a month delayed, but here I am!

Disclaimers

Let’s get one thing out of the way before I go further.

Only the most recent major version of WordPress is supported.

Though security patches are occasionally backported to older versions of WordPress (currently all the way back to the 4.1 branch), this is not guaranteed and is only done as a courtesy. You are strongly encouraged to keep your sites updated and running the latest version of WordPress whenever possible. Auto-updates make this really easy!

OK, now that I’ve made that clear, one note about my setup.

If you’re a newer contributor, or even an experience one that only contributes to the next upcoming WordPress release, my setup will seem overly complicated. And you’re right! It’s not, you it’s me, and I don’t recommend this setup to the average contributor or even committer. But hopefully there are is something in here that you find useful.

Contributing Environment Setup

I have three folders on my machine that I use for contributing and/or committing to WordPress Core.

wordpress-svn Folder

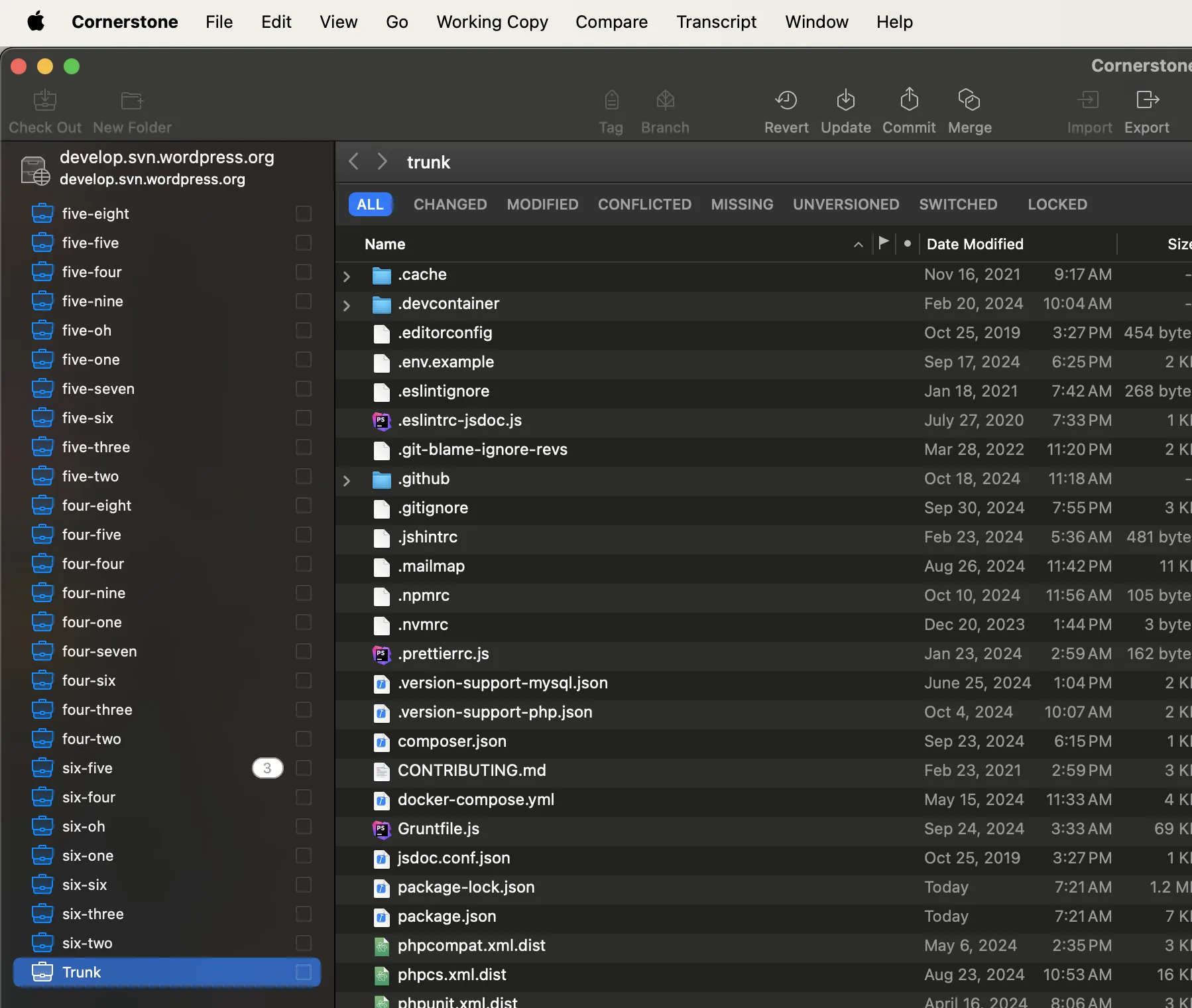

As a Build/Test Tool component maintainer and a member of the Security Team, I’m often committing to many different branches of wordpress-develop. Sometimes all of them in the same day! Because any of the (soon to be) 27 branches (4.1-6.7) could be updated at any time, the build and test tooling needs to be maintained.

The way I have found that works best for me to manage and clearly know which branch I’m working on is to have a separate SVN checkout of each branch with the verbal representation as the folder name. The wordpress-svn folder is where I keep these.

wordpress-svn

├── five-eight

├── five-five

├── five-four

├── five-nine

├── five-oh

├── five-one

├── five-seven

├── five-six

├── five-three

├── five-two

├── four-eight

├── four-five

├── four-four

├── four-nine

├── four-oh

├── four-one

├── four-seven

├── four-six

├── four-three

├── four-two

├── six-five

├── six-four

├── six-oh

├── six-one

├── six-seven

├── six-six

├── six-three

├── six-two

├── three-eight

├── three-nine

├── three-seven

├── three-six

├── trunk

Having separate checkouts also allows me to stage changes to multiple branches ahead of time. This is very helpful in the days leading up to a security release so I don’t have to deal with switching branches and applying patches when I’m responsible for committing the updates and/or version bumps to prepare the release.

I had a setup similar to this even before I was a committer. I used to manage this through a vvv-custom.yml file when that was my contribution environment (see my old blog post about this). It was useful to have previous versions readily available for taking screenshots, or testing how something used to work in older versions of WordPress. When I switched away from VVV, I moved to my current setup which relies on the local Docker environment included in trunk. Because all of my folders have different names, I can have a unique local environment for all of them (though only one can be running at once).

This wordpress-svn directory is where I perform all of my commits to WordPress. I have a script that I use to reset and update these checkouts. More on that later.

I primarily use this folder for committing. But on occasion, I will perform some final testing.

wordpress-develop Folder

The wordpress-develop folder is just a clone of my official wordpress-develop Git mirror fork on GitHub. This is where I spend the majority of my time writing, testing, and reviewing code. GitHub is arguably the most convenient place to collaborate on contributions to the WordPress code base, and it’s where the majority of contributors are the most comfortable.

Though suggested changes will not be merged on GitHub (SVN is the canonical source of truth), pull requests are great for suggesting improvements and changes, asking questions, and confirming that all of Core’s automated testing completes successfully without issue. You can read more about how this contributor workflow works in the Core Handbook.

wordpress-build Folder

This folder has a clone of my WordPress Build repository fork, which contains the build files that are eventually shipped in each release of WordPress. I use this folder when I need to compare the results of changes to any build scripts against the current state of the built code.

For example, when updating npm dependencies such as webpack, uglify-js or postcss, it could be helpful to confirm no new files are introduced or that only the files expected to change actually do.

My Committing to WordPress Workflow

In my wordpress-develop folder:

- Create a pull request to wordpress-develop, review pull request from someone else, or some combination of the two.

- Confirm automated testing through GitHub Actions.

- Test locally and confirm intended behavior, no unintended consequences of changes, etc. using the local Docker environment.

- Leave a review or comment on the pull request.

Switch to Trac and my wordpress-svn folder.

- Check for any uncommitted changes using

svn diff. - Anything uncommitted is usually not needed. But if there’s anything I want to save, I’ll create a patch using

svn diff > patch.diff. Otherwise I’ll wipe it out withsvn revert -R .. - Create a clean, up to date environment by running

svn revert -R . && svn up. - Apply the patch to be committed using

grunt-patch-wordpress.- For patches attached to a Trac ticket, running

npm run grunt patch:12345will list all patch attachments on ticket 12345 to select the one you want to apply. - For GitHub PRs, running

npm run grunt patch:##PR_URL##will apply the diff for that specific pull request. - In some situations,

grunt-patch-wordpresscan’t properly apply the PR diff (when there are changes in the.githubdirectory, for example). In this case, I’ll usually:- Add

.diffto the PR’s url. - Save the patch to my machine.

- Use

svn patch patch.diffto apply the patch on my own.

- Add

- For patches attached to a Trac ticket, running

- Use

svn diffto review the local changes after applying the patch to confirm everything looks good. - If necessary, spin up the local Docker environment to triple check the changes work as intended.

- Maybe another

svn diffif I’m having any doubts about why I’m partially responsible for maintaining software that ships to tens of millions of sites.

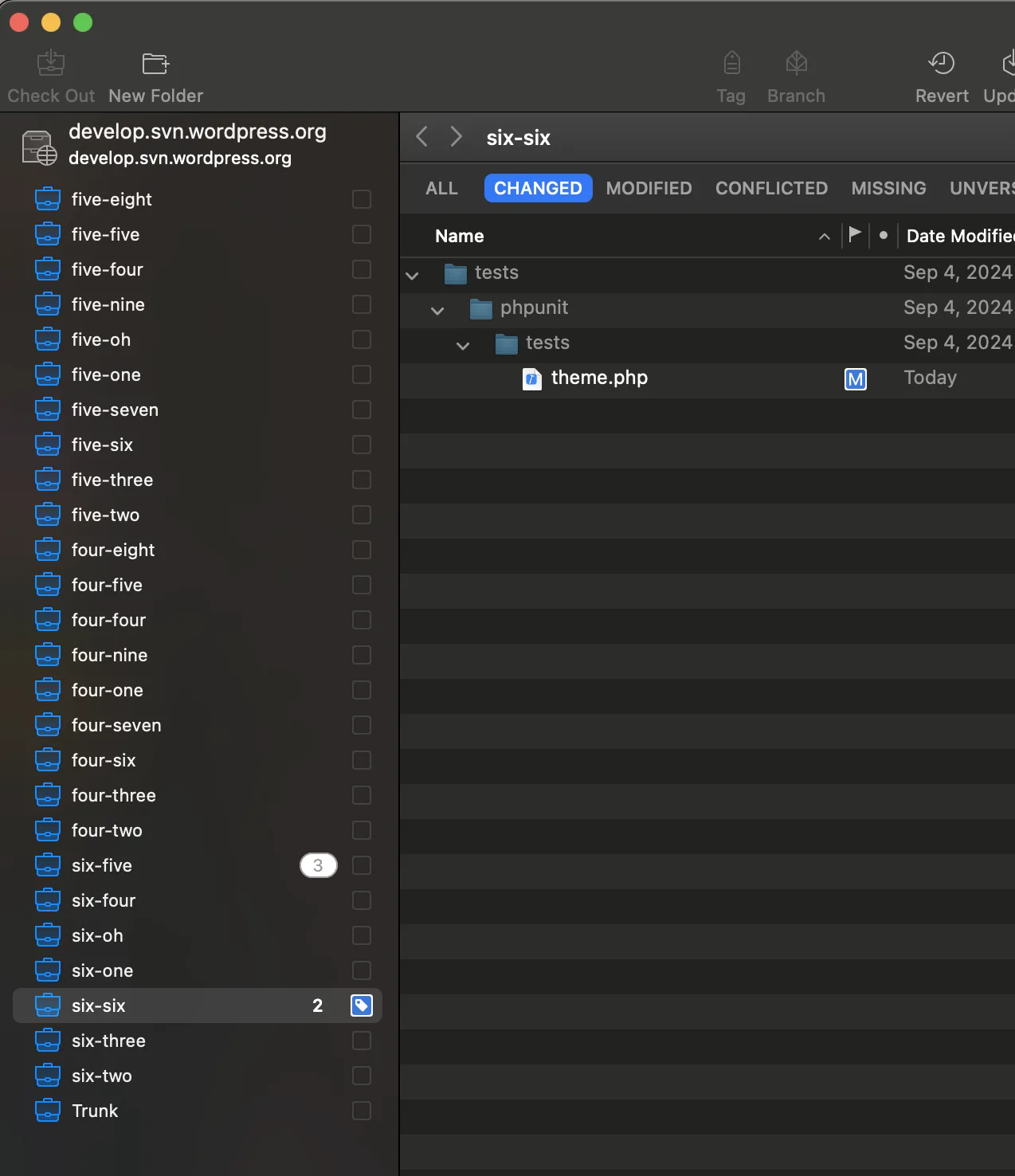

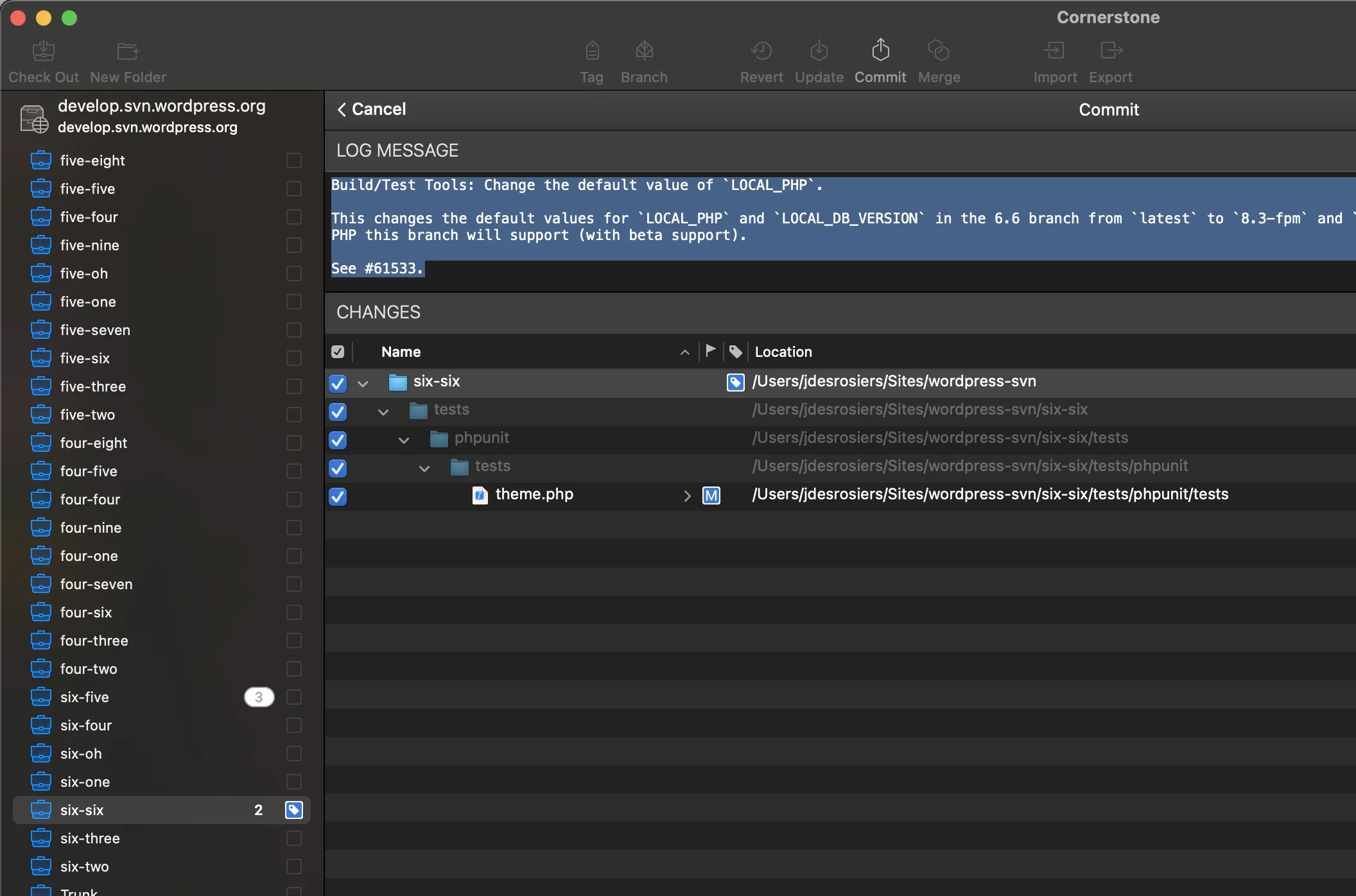

For the actual committing to WordPress part, I use the Mac-based Cornerstone Subversion client. I have all of my local SVN checkouts for wordpress-develop added to the app.

While I use svn diff to triple check everything before committing, I really like being able to also see a visual overview of the changes that will be made in the commit. This is especially helpful when moving, adding, or deleting files, and when performing a backport commit (which is essentially a merge). The screenshots below show a staged backport commit, note the blue “Tag” icon indicating that the svn:mergeinfo has been updated.

I also like that the log message input preserves anything you type if you cancel and go back to commit in the future. I find that helpful to build a message over time or while waiting for tests to finish running. This also allows me to stage multiple commits to multiple branches while preparing for a security release or other coordinated backport effort.

After a commit, it pre-populates the field with the previous commit message, which helps me remember the correct order of the required information (is “Fixes” before or after “Props” ?).

That’s pretty much it!

Miscellaneous Notes

I mentioned above that I have a script for resetting and updating my SVN checkouts. I’ve shared this in a Gist. Given the folder structure I shared above, it will attempt to remove all node_modules folders and ensure the proper branch is checked out with the latest changes for each version specified. I also have a script that pulls in changes from the Git mirror into my fork.

I have aliases set up for these scripts, so I only have to remember wpup and wptrunkup. I don’t run these often, though, usually just after a security release. At least daily I do run git fetch --all && git merge upstream/trunk to bring my primary branch up to date, though.

Conclusion

As I said at the beginning, this setup is probably too much for the large majority of contributors. And it’s what works specifically for me. But hopefully you see something that is useful for your own contributing workflow. There’s a page in the Core Handbook that will be updated as more committers share their committing workflows. But here are links to the posts that were published before mine in a much more timely fashion!

- Aaron Jorbin

- David Baumwald

- Dennis Snell

- Drew Jaynes

- Felix Arntz

- Joe McGill

- Marius Jensen

- Pascal Birchler

And finally, don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Deep down, we’re all human. Wear them as a badge of honor.

Featured image credit: CC0 licensed photo by Jeff Golenski from the WordPress Photo Directory.

Leave a Reply